This post was originally published at Medium.com on August 28, 2015.

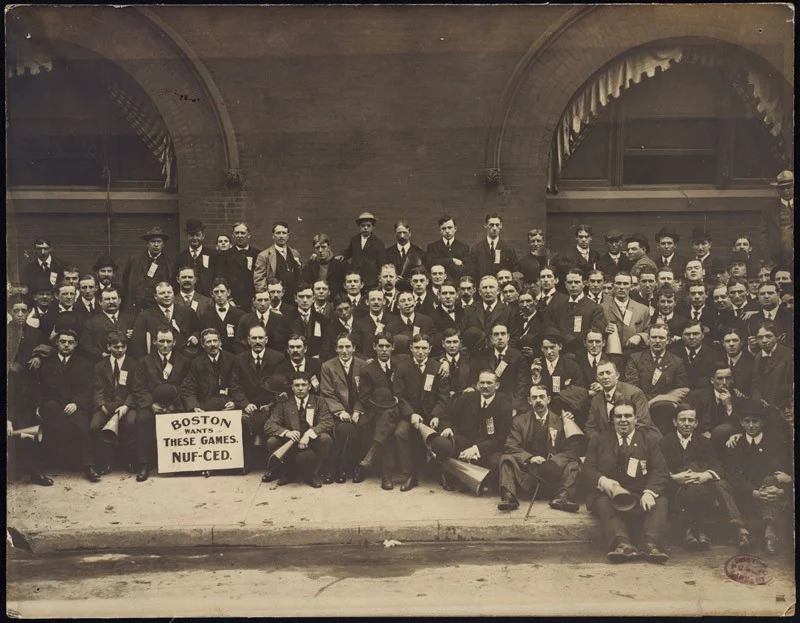

Somewhere in the picture above, there might be a man named Leo Levy. His name appears on a Boston Herald list of “Royal Rooters” traveling to New York for the pivotal final series of the 1904 American League baseball season, and this picture was taken during that trip. No other mention of him appears in either the Herald or the Boston Globe’s coverage of the series, but he does pop up in a Herald article on August 13, 1897, when theHerald singled him out as “one of the old guard on the Boston grounds.” The same article also identifies a man named Sam Levy as both a member of the “cloak brigade” and “one of the good old Boston rooters in the capacious grand stand.” Sam’s presence at games is additionally noted in 1890, 1891, and 1894 articles, but that’s it. No other Globe or Herald articles ever again mention either Levy in connection with Boston baseball.

I’ve been researching Leo and Sam Levy, along with several other Bostonians of the same period, for my new project on the Royal Rooters, a group of baseball fans who became nationally celebrated between 1897 and 1918 for their fervor and their raucous cheering tactics. I’m interested in why this early group of noted sports fans chose to root for the city’s professional baseball teams, but also in the fact that behind the group’s predominantly Irish-American leadership (which has been recognized previously by Ken Burns and other students of the early professional game) lay a diverse group that included old-line Brahmin Protestants, Jews, a few women, and perhaps even African Americans. I’m fascinated by the contrast between this intermingling in the stands and barrooms and the stark divisions between Protestants and Catholics that existed at the time throughout the city and even within the Red Sox clubhouse.

So far, Sam and Leo Levy seem to be the best avenues into the relationship between Boston’s Jewish community and professional baseball during this period, but the clues about their lives remain sparse. I was hoping they might be related, but census research suggests that is not the case. There was a Sam Levy identified as a Boston pinochle champion in 1897, one who served as a groomsman at a wedding in Roxbury (where many of the Rooters worked and lived) in 1901, and one selling cloaks at 564 Washington Street in Roxbury in 1904. A Leo Levy was recognized on the society page of the Globe for stopping in Saratoga in 1901, and presented as an entertainer at a capmakers’ union benefit in 1903. At this point, though, I’m still not even sure whether these are the same men.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that I am having trouble finding information on these men who lived relatively obscure lives over a century ago. Yet this pattern persists even in the lives of celebrated Rooters. Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevey is omnipresent in the city’s newspapers and makes regular appearances in the national sporting press, during the first two decades of the twentieth century but finding additional information about him beyond these sources has proven challenging. Even John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, U.S. Congressman, Mayor of Boston, and grandfather of President John F. Kennedy, thus far appears to have left behind a remarkably small paper trail relative to his political stature.

This scarcity of evidence is a new experience for me; in my last project, one of my primary challenges was whittling down the overwhelming collection of available resources into a manageable set of data. Thus it’s possible that I need to develop more effective research strategies, or that the information I am seeking is in the large collections of materials that remain on my to-do list. Yet I am starting to wonder whether there is a broader issue at play here. Why was it easier to find information about relatively obscure editors and ministers who lived over two hundred years ago than about relatively famous men who lived into the mid-twentieth century?

One archivist has suggested that local politicians such as McGreevey or Fitzgerald may have been reluctant to commit their ideas or practices to paper, and I think he may be on target. With the rapidly expanding world of digitized historical collections of printed material, the possibilities for finding information are exponentially greater than they were even a dozen years ago when I was researching my dissertation. This wealth of information sometimes makes us believe that we can recover the stories of anyone who lived within communities where printed materials were omnipresent. But for individuals such as the Levys, who may not have been fully engaged with these print-centered cultures, or those such as McGreevey and Fitzgerald who may have chosen to keep parts of their lives hidden from those cultures, that recovery process may be much more challenging. It’s important to remember that even as we dig deeper into the past through more creative practices and more accessible information, we’re still only scratching the surface of those worlds that can seem so deceptively close to our own.

The Royal Rooters picture above is printed courtesy of theMichael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevey Collection of the Boston Public Library, which is available online athttps://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/collections/72157623971712149/.